Patent Review: Multiple Path Acoustic Wall Coupling for Surface-Mounted Speakers

This article reviews a patent awarded to Paul Wayne Peace Jr. and Derrick Rodgers, on behalf of Harman International Industries. The patent describes a surface-mounted loudspeaker design that mitigates the interference between direct low-frequency (LF) energy and reflected LF energy by breaking the LF energy from an LF driver into multiple paths using one or more of waveguides, driver load plates, and enclosure ports to diffuse the reflected energy and minimize frequency response errors.

Multiple Path Acoustic Wall Coupling for Surface-Mounted Speakers

Patent/Publication Number: US 2019/0020937

Inventor(s): Paul Wayne Peace Jr. (Viejo, CA); Derrick Rodgers (Altadena, CA)

Assignee: Harman International Industries, Inc.

Filed: January 14, 2016

Current CPC Class: H04R 1/22 20130101

Published: January 17, 2019

Number of Claims: 20

Number of Drawings: 9

Abstract from Patent

A surface mounted loudspeaker design is provided that mitigates the interference between direct low-frequency (LF) energy and reflected LF energy by breaking the LF energy from an LF driver into multiple paths using one or more of waveguides, driver load plates, and enclosure ports to diffuse the reflected energy and minimize frequency response errors. One or more embodiments of the present disclosure provides a loudspeaker have multiple acoustic exits strategically designed and located to generate, for example, three major wave front arrivals — 2 source and 1 reflection — at target angles with favorable lag times, mitigating the cancellation notching and frequency errors that occur in conventional loudspeaker designs.

Independent Claims

1. A loudspeaker comprising: a speaker enclosure adapted for surface-mounting and including a front surface having at least one front acoustic exit facing a target direction and a rear surface having at least one rear acoustic exit adapted to face a wall surface; and a low-frequency (LF) driver disposed in the speaker enclosure and adapted to emit LF acoustic energy that exits at least the front acoustic exit and the rear acoustic exit, the LF acoustic energy exiting the front acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction forming a first LF energy wave front, the LF acoustic energy exiting the front acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface forming a second LF energy wave front that lags the first LF energy wave front, the LF acoustic energy exiting the rear acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction combined with the LF acoustic energy exiting the rear acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface forming a third LF energy wave front that arrives between the first LF energy wave front and the second LF energy wave front.

9. A loudspeaker comprising: a speaker enclosure including a front surface having a front acoustic exit, at least one side surface having a side acoustic exit, a rear surface having at least one rear acoustic exit, and a bottom surface having a bottom acoustic exit; a low-frequency (LF) driver disposed in the speaker enclosure and having a radiating surface adapted to emit LF acoustic energy and a radiating surface opening defined by an outer circumference of the radiating surface; an LF waveguide defining a first radiation path for the LF acoustic energy, the LF waveguide having a proximal opening positioned adjacent to the LF driver and extending away from the LF driver to a distal opening to define the first radiation path there though, the proximal opening having a proximal opening area that is smaller than a radiating surface opening area to define a second radiation path for the LF acoustic energy around the LF waveguide and out the front acoustic exit and the side acoustic exit; and a load plate directly in front of a bottom portion of the radiating surface and adjacent the LF waveguide to deflect a portion of the LF acoustic energy along a third radiation path to the rear acoustic exit and the bottom acoustic exit.

15. A method for radiating sound comprising: providing a speaker enclosure including a front surface having at least one front acoustic exit facing a target direction and a rear surface having at least one rear acoustic exit adapted to face a wall surface; providing a low-frequency (LF) driver disposed in the speaker enclosure and adapted to emit LF acoustic energy that exits at least the front acoustic exit and the rear acoustic exit; generating a first LF energy wave front from the LF acoustic energy exiting the front acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction; generating a second LF energy wave front that lags the first LF energy wave front from the LF acoustic energy exiting the front acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface; and generating a third LF energy wave front that arrives between the first LF energy wave front and the second LF energy wave front from the LF acoustic energy exiting the rear acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction combined with the LF acoustic energy exiting the rear acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface.

Reviewer Comments

Over the last few decades we have seen a number of alleged solutions to the amplitude response notch/cancellations caused by a loudspeaker interacting with nearby boundaries. We have reviewed many of these in past issues of Voice Coil.

I still remember the first paper that got me thinking about this issue, which was written by the brilliant Edward C. Wente in 1935 in Issue 1 of Volume 7 of the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, “The Characteristics of Sound Transmission in Rooms.”

As mentioned in previous Voice Coil patent reviews, it was Roy Allison who is known for popularizing this issue in his 1974 paper, “The Influence of Room Boundaries on Loudspeaker Power Output,” presented at the 48th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society. The theoretical form of Allison’s work was derived from the mathematic formulas presented by Richard Waterhouse in his 1955 and 1958 papers in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, “Interference Patterns in Reverberant Sound Fields” and “Output of a Sound Source in a Reverberation Chamber and Other Reflecting Environments.”

The Waterhouse formulation, or the “Allison Effect,” as it has come to be known, teaches that for a single boundary reflection, the resultant system attenuation dip, with the source quarter-wavelength from the boundary (half-wave round trip for the signal to the boundary and back to the loudspeaker), will be only about one decibel. For two perpendicular boundaries, each the same quarter-wavelength distance from the source, the dip prediction is -3 dB, and for three perpendicular boundaries, each the same quarter-wavelength distance from the source the dip prediction is -11.5 dB.

As Allison explained, the effect is based on the notion that the reflected sound waves actually alter the emissions from the loudspeaker by arriving back at the loudspeaker out of phase with the loudspeaker active driver, reducing the pressure on the driver’s surface, causing a reduction in the radiation resistance, wherein the driver is effectively working in a partial vacuum at the dip frequency…the effect is local to the driver output.

Alternatively, there is a school of thought that suggests that the cancellation result is based on a “specular boundary reflection” interacting with the direct output at the reception point (microphone or listener). In the case of a floor boundary, instead of the floor reflection having a half-wave round trip from the floor boundary causing a decrease in output at the driver itself, the direct sound from the driver combines at the reception point with a floor reflection occurring midway between the loudspeaker source and the reception point causing a dip in the response at the frequency for which the floor reflection pathway is a half-wavelength longer than the direct sound from the loudspeaker.

Part of the conflict between the two boundary interaction “theologies” is that even though the Waterhouse math results in a single boundary dip amplitude of approximately 1 dB, there are measureable examples of single boundary reflections, such as the so called “floor bounce” that can exhibit cancellation depths of at least 6 dB.

In the case of the floor boundary, the two effects will tend to happen at two separate frequencies and the output may exhibit both effects separately. Whereas for a single boundary reflection from the wall behind the loudspeaker, both effects will tend to occur at the same frequency since the pathway from the loudspeaker to the wall is the same length as the differential between the direct and reflected pathways arriving at the reception point.

It does not appear that an analysis and comparison of the two different explanations for boundary reflections has appeared in the acoustical literature. That said, Roy Allison clearly had the belief that the Waterhouse formulation was the dominant effect, while others, such as Jorma Salmi and Anders Weckström, in their 1982 and 1983 Audio Engineering Society (AES) papers, “Listening Room Influence on Loudspeaker Sound Quality and Ways of Minimizing It” and “A New, Psychoacoustically More Correct Way of Measuring Loudspeaker Frequency Responses” tend to support the specular explanation, with such differences as deeper cancellation depth, a shift in frequency, and a broader band of comb filtering beyond the 0.75 wL limit of Allison.

Based on the graph shown in Figure 2, citing the depth of cancellation from a single boundary as being on the order of -24 dB, the inventor of the patent application under review here appears to be operating under the assumption of a specular-based explanation as opposed to Allison/Waterhouse as the dominant theory regarding causation of the impact of the boundary reflection issue it is attempting to correct by way of a new loudspeaker layout.

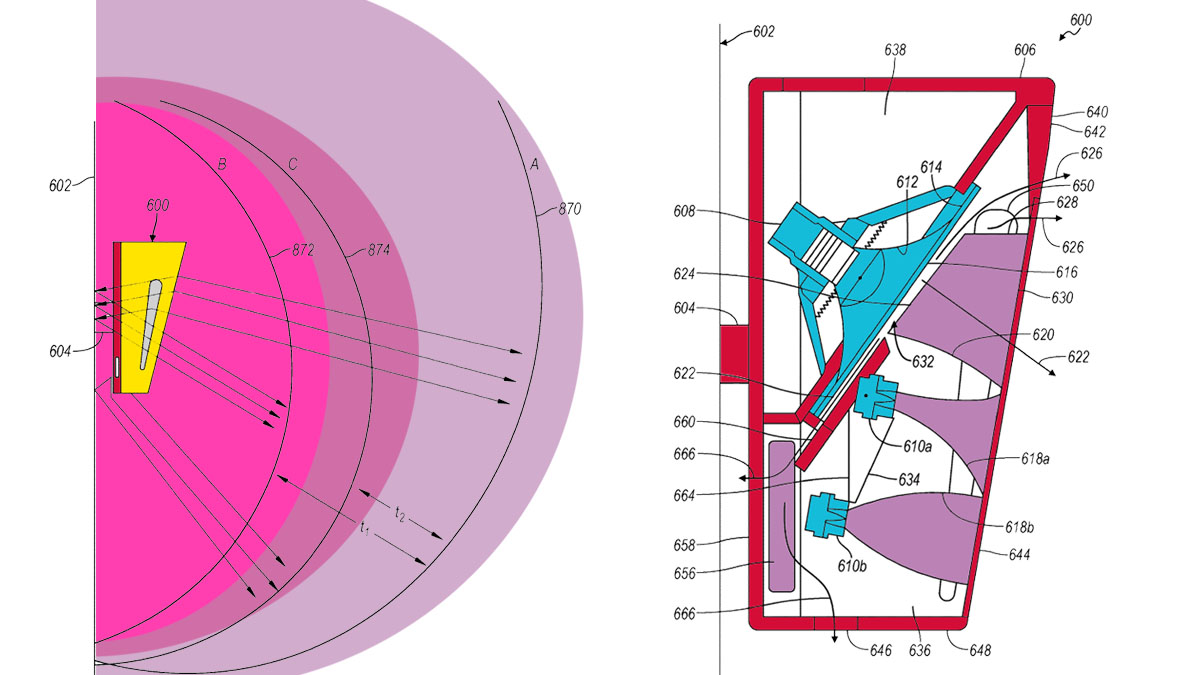

The publication states that a surface-mounted loudspeaker generates two distinct acoustic energy arrivals — one direct from the transducer and the other reflected from the surface to which it is mounted. The interference of the reflected energy with the direct energy is primarily destructive by creating dramatic frequency response errors. The frequency of these errors is directly related to the time difference between the two energy arrivals “at the listener,” as opposed to “at the loudspeaker” as would be the case in the Waterhouse formulation.

To paraphrase the inventor description of the invention, the device comprises a speaker enclosure and a low-frequency driver mounted in the speaker enclosure. The speaker enclosure is adapted for boundary surface-mounting and includes a front surface having at least one front acoustic exit facing a target direction and a rear surface having at least one rear acoustic exit adapted to face a wall surface.

The low-frequency (LF) driver is adapted to emit LF acoustic energy that exits at least the front acoustic exit and the rear acoustic exit. The LF acoustic energy exiting the front acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction forms a first LF energy wave front. The LF acoustic energy exiting the front acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface forms a second LF energy wave front that lags the first LF energy wave front. The LF acoustic energy exiting the rear acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction combined with the LF acoustic energy exiting the rear acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface forms a third LF energy wave front that arrives between the first LF energy wave front and the second LF energy wave front.

As in one example, the first LF energy wave front may have a magnitude of 0.80. The second LF energy wave front may have a magnitude of 0.50 and lag the first LF energy wave front by 3.70 ms. The third LF energy wave front may have a magnitude of 1.65 and lag the first LF energy wave front by 1.35 ms.

The enclosure may further comprise at least one side surface having a side acoustic exit. The LF acoustic energy exiting the side acoustic exit and radiating in the target direction may form part of the first LF energy wave front, while the LF acoustic energy exiting the side acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface may form part of the second LF energy wave front that lags the first LF energy wave front. The at least one side surface having a side acoustic exit may include two side surfaces, each side surface having the side acoustic exit.

The enclosure may further include a bottom surface having a bottom acoustic exit. The LF acoustic energy exiting the bottom acoustic exit and radiating directly in the target direction combined with the LF acoustic energy exiting the bottom acoustic exit and reflecting off the wall surface may form part of the third LF energy wave front that arrives between the first LF energy wave front and the second LF energy wave front.

The loudspeaker may further include a LF waveguide coupled to the LF driver defining a first radiation path for the LF acoustic energy, wherein at least one front acoustic exit includes the LF waveguide. The front acoustic exit may include a front opening in the speaker enclosure above the LF waveguide. The LF waveguide may have a proximal opening positioned adjacent to the LF driver and extending away from the LF driver to a distal opening to define the first radiation path. The proximal opening may have an opening area that is smaller than a radiating surface opening area to define a second radiation path for the LF acoustic energy around the LF waveguide and out the front opening.

The loudspeaker may further include a load plate directly in front of a bottom portion of the radiating surface and adjacent to the LF waveguide to deflect a portion of the LF acoustic energy along a third radiation path to the rear acoustic exit.

In one embodiment, the target axis of the loudspeaker system may be between 30° and 60° down from horizontal to further create a different reflective path length above the loudspeaker from that radiating below the loudspeaker.

As can be seen by the description of the inventive system the goal is to vary the amplitudes and differentiate the path lengths of a number of separate wave fronts that reflect of the nearest boundary surface behind the enclosure, and launch forward to combine with the direct sound pathway to the listener. When the loudspeaker dimensions are large enough to create reflective path lengths that are differentiated by a significant percentage of a primary reflective path length then the summation of the all the reflections potentially should be distributed enough to substantially minimize the ripple in the system response caused by the reflections interacting with the direct response.

Figure 3 shows a corrective response of the invention with less than 1 dB of ripple in the reflection range, plus standard lower frequency boundary gain for frequencies corresponding to boundary distances of less than a quarter-wavelength. If this level of reflection correction can be achieved by the configurations disclosed, the system represents a very useful format for accurate reproduction in boundary-coupled systems. VC

This article was originally published in Voice Coil, May 2019

Source link

.png)

.jpg)