Only Known Photos of World’s First Computer Programmer Ada Lovelace Go to Auction

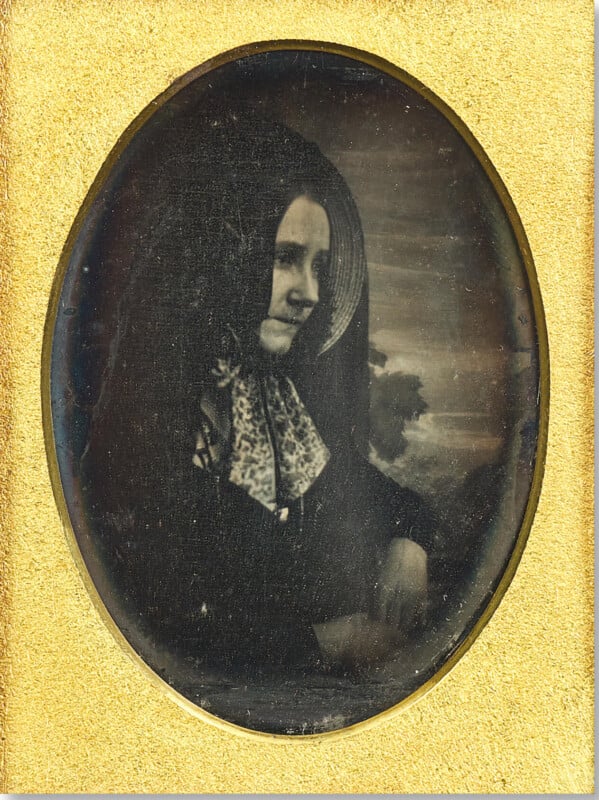

The only known photographs of Ada Lovelace — who wrote the world’s first computer program in the mid-1800s — are estimated to fetch $162,000 at auction.

The extremely rare images of Lovelace are up for auction at Bonhams in London, U.K., as part of its “Fine Books, Maps & Manuscripts” online sale next week (June 19).

The three images are the only photographs believed to be in existence of Lovelace, the pioneering mathematician and writer who is widely regarded as the world’s first computer programmer. The photographs come with an estimate of $108,000 to $162,000 (£80,000 to £120,000).

According to Fine Books Magazine , the lot includes two portraits by Antoine Claudet who was a former pupil of the inventor of the daguerreotype Louis Daguerre.

These daguerreotypes were taken by Claudet around the pivotal year of 1843 when Lovelace published her celebrated paper on Charles Babbage’s proposed mechanical general-purpose computer the Analytical Engine. She was the first to recognize that the machine had potential and applications beyond mere calculation.

Claudet photographed Lovelace in two different attires, seated in front of the same elaborate painted backdrop of foliage. Claudet learned photography from Daguerre in the late 1830s, before establishing his first daguerreotype studio in London in 1841.

Claudet photographed several other scientists including Babbage, physicist Michael Faraday, and Sir Charles Wheatstone and it is likely that one of these Lovelace was recommended to the photographer by one of these eminent individuals. According to Bonhams, Lovelace was particularly intrigued by photography and wrote presciently in an unpublished piece that “it is as yet quite unsuspected how important a part photography is to play in the advancement of human knowledge.”

The lot also includes an anonymous photo of Henry Wyndham Phillips’ painting of Lovelace towards the end of her life in August 1852 when her health had seriously worsened.

All three photographs of Lovelace have previously appeared in exhibitions over the last decade at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the National Portrait Gallery in London.

The Life and Legacy of Computer Pioneer Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace was born in 1815 as the only legitimate child of the famous poet Lord Byron and his wife Anne Isabella Milbanke. Her parents separated when she was just five weeks old, so Ada was raised mainly by her mother and grandmother.

Her mother worried Ada might inherit Byron’s wild and artistic nature, so she made sure Ada studied science, math, and logic very seriously. From a young age, Ada loved machines and spent hours dreaming up inventions and reading about science.

In 1833 Ada Lovelace met the inventor and mechanical engineer Charles Babbage, who had designed a calculating machine called the Difference Engine. Lovelace was inspired by the prototype of the Difference Engine — a mechanical calculating machine, or by today’s standards, a basic calculator.

Lovelace and Babbage became lifelong friends and correspondents, and Ada studied Babbage’s plans for a new invention, the Analytical Engine, in great detail.

Between 1842 and 1843, Ada translated an Italian article about the Analytical Engine by Luigi Menabrea and added her own detailed notes. In these notes, she wrote the first-ever algorithm meant to be run by a machine. Lovelace explained the machine’s potential for general-purpose computation and included step-by-step instructions for calculating a sequence of Bernoulli numbers — which is often called the first published computer program.

Ada died in 1852 at age 36. Although the Analytical Engine was never built, her ideas survived and later helped shape important developments in computing and artificial intelligence, influencing pioneers like Alan Turing.

Lovelace’s plans for the Analytical Engine were never realized and Babbage never built the machine. However, Lovelace’s notes survived, and, in the 1940s, became one of the foremost documents that helped shape Alan Turing’s paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence — a seminal work in the field of AI.

Bonham’s “Fine Books, Maps & Manuscripts” sale ends on June 19.

Image credits: All photos by Bonham’s

Source link